Detectives called it an “unnecessarily savage attack” with several ribs broken and a punctured lung.

“Byberry Guard Held in Death,” Berwick Enterprise, February 5, 1940: 7.

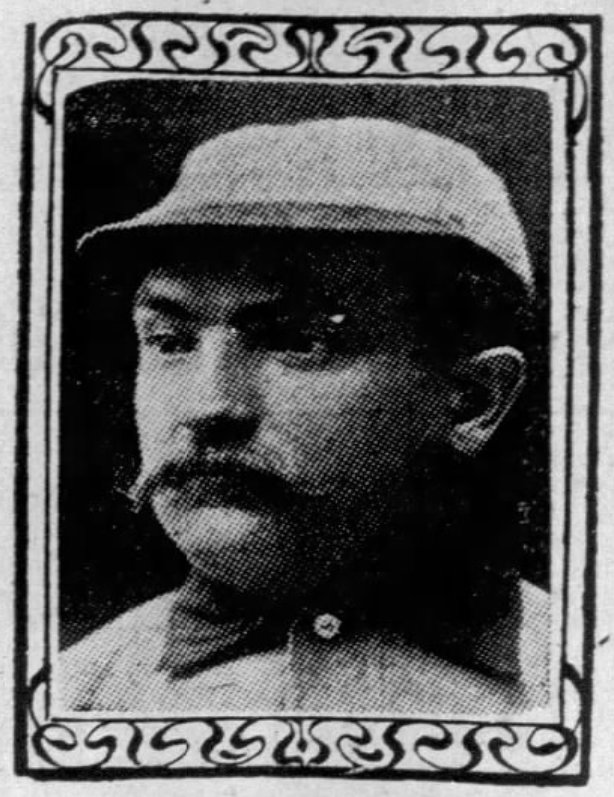

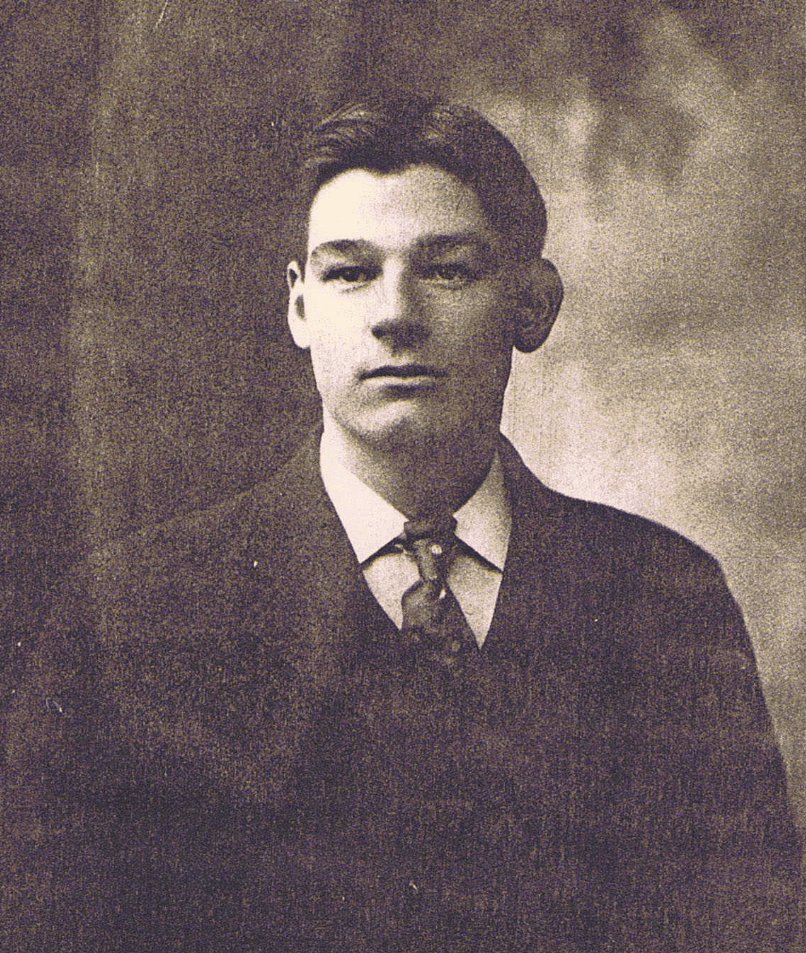

Former Negro League pitcher Alexander Albritton was killed by Frank Lewis Weinand in a melee of sorts at the Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry – an insane asylum. Albritton’s Pennsylvania death certificate is marked “inquest pending”… His broken remains were buried in Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.

The incident occurred on January 31 when Weinand asked Albritton to sweep a room and Albritton chose to respond by smacking Wienand over the head with the broom, drawing blood. Weinand, who outweighed Albritton by some 70 pounds, proceeded to fight back and, with the help of two other attendants, subdued Albritton. At the time doctors claimed they saw nothing seriously wrong with Albritton. However, when he died three days later on February 3, 1940, they found broken ribs and other injuries, including a punctured lung which was the cause of Albritton’s death – calling into question what kind of medical checkup Albritton received.

“The crux of the early probes was centered around determining why Albritton did not receive medical attention. Dr. H. C. Woolley, superintendent at Byberry, declared that a physician immediately examined Albritton after the beating and found nothing wrong with him. On Saturday at 1 p.m., Albritton was stripped for a routine examination and still nothing was found wrong with him, Dr. Woolley attempted to explain. But at 2 p.m. an attendant found him dead on a bench.”

“Insane Patient Dies After Brutal Beating at Byberry,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 10, 1940: 1, 4.

Weinand was arrested, charged with murder and held without bail. Eventually a $1,000 bail was announced and paid… Best as I can tell, Weinand’s case never went to trial – there were no articles proclaiming the innocence or guilt of Frank Weinand in subsequent months, even though a trial was initially scheduled for April 1940.

When Governor Arthur James visited in March, 1939, he “…contrasted treatment of the mentally ill there with the comparatively luxurious care given criminals at the State Penitentiary at Graterford, which he also visited last week.”

“At Graterford,” he said, “they go to the extreme of providing for all sorts of comforts and advantages, while, on the other hand, the poor unfortunates at Byberry have been receiving treatment that can only be described as inhuman.”

“James is Shocked on Byberry Visit,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 21, 1939: 2.

Not to absolve Weinand, the Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry was horribly overcrowded and had serious administration issues. At some point, they moved 2000 inmates to different locations as the buildings supported about 3500 patients and by 1938 there were more than 5500 patients. Patients weren’t receiving treatment, the place was horribly understaffed, it was a huge fire hazard. After a series of horrible reports made the Philadelphia Inquirer the state tried to step in and change things. Change, however, was slow. In fact, on the day Albritton was found dead sitting upright on a stool, another inmate also died in a fight with another violent inmate within an hour of finding Albritton’s lifeless body. One newspaper article said there was a death there every week or ten days. Byberry’s reputation never improved and it finally closed in the 1980s.

Life in Professional Baseball

Albritton was a pitcher of some skill, pitching for the Baltimore Black Sox, the Washington Potomacs, and the Wilmington Potomacs, all three teams now recognized as major league teams in the Negro Leagues of the 1920s. He also pitched for the famous Hilldale Daisies during his decade-plus life in professional baseball.

Alex was the youngest of four children born to Charlotte Henrietta and D. Mathew Albritton; both parents were born into slavery in the Carolinas. Mathew worked as a brazier and a farm laborer in subsequent years; Alex was born in Live Oak, Florida on February 12, 1892, but the family moved to Georgia for the next two decades. (Live Oak is in an area of Florida that is arguably South Georgia…)

Albritton’s path through professional baseball wound northward from the small towns of the deep south to the large cities of the Mid-Atlantic… By the mid 1910s, he was pitching for teams in Texas, including stops in Boyd and for the Armours of the North Texas League. In 1916 he was on a team of southern all-stars. One comment caught my attention: “Many collegians were seen in the line-up, which not only made them famous as a baseball team, but gave them popularity for being gentleman.” (“Giants Onslaught Buries Lincoln Stars,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1916: 8.) Alex was an exception in that according to the 1920 US Census, he could neither read nor write.

In 1919 he’s pitching for the Baltimore Black Sox and eventually he moves to the Pennsylvania (or Philadelphia Giants) by the end of that season. He faced Hilldale then. Albritton joined the Buffalo Stars before jumping to the Washington Braves for 1921. There, he had opportunities to play with and against Grant “Home Run” Johnson. He nearly jumped to the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City, but was swiped away by the Hilldale Daisies where he won seven of nine decisions and batted .286 against all competition. However, in the Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, James A. Riley noted, “…despite being a hard worker and always ready to pitch, never really made it big.” Riley added that Albritton could beat the white semi-pro teams, but was less effective against the top Negro League teams.

In 1924, the Brooklyn Cuban Giants made a tour of the south in the spring, playing so well that at one point the Giants had 18 wins in 24 games. “Alex Albritton, the spit ball artist, formerly of Hilldale, Baltimore Black Sox and Washington Potomacs, is the pitching ace of the Giants, with a record of 8 wins and 1 lost.” (“Brooklyn Cuban Giants are Playing Sensational Ball in the South,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 24, 1924: 10.)

At this point, Albritton joined the Washington and Wilmington Potomacs before leaving professional baseball.

Albritton married Marie Julia Brooks around 1916; they had six children. For most of their married life the family lived in the Philadelphia area. There, Albritton worked as a laborer in a paint factory and later as a laborer for a building contractor. At some point in the late 1930s, whatever problems he developed led to his being sent to the Pennsylvania State Hospital.

Albritton was said to suffer delusions that he was the father of President Roosevelt and that God was always speaking to him.

“Insane Patient Dies After Brutal Beating at Byberry,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 10, 1940: 1, 4.

Alex Albritton was nine days shy of his 48th birthday when he was killed.

Sources:

1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940 US Census

PA Death Certificates

“Boyd Ball Team Coming for Games,” Wise County Messenger, May 29, 1914: 1.

“Crucial Test for North Texas Sunday Leaguers,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 30, 1914: 19.

“Giants Onslaught Buries Lincoln Stars,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1916: 8.

“Chester Baffled by Sox Twirler,” Camden Daily Courier, August 18, 1919: 11.

“Capitals to be Idle Until Next Thursday,” Washington Evening Star, April 24, 1921: 29.

“Buffalo Stars Beat Braves, 2-1,” Washington Herald, May 16, 1921: 6.

“Newark American Giants’ Lineup Nearly Complete,” Black Dispatch (Oklahoma City), April 10, 1924: 6.

“Brooklyn Cuban Giants are Playing Sensational Ball in the South,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 24, 1924: 10.

“To Relieve Overcrowding at Byberry,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 27, 1939: 6.

“James is Shocked on Byberry Visit,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 21, 1939: 2.

“Byberry Guard Held in Death,” Berwick (PA) Enterprise, February 5, 1940: 7.

“Exonerate Attendant in Death of Inmate,” Berwick (PA) Enterprise, February 7, 1940: 2.

“Insane Patient Dies After Brutal Beating at Byberry,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 10, 1940: 1, 4.

“Held Without Bail,” Shenandoah Evening Herald, February 15, 1940: 1.

“Staff at Byberry Called Inadequate,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 15, 1940: 2.

“To Push Probe in Death of Insane Man,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 17, 1940: 1.

“Released on Bail,” Shenandoah Evening Herald, February 21, 1940: 1.

“Byberry Guard Freed,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 2, 1940: 3.

“Institution at Byberry is Again Under Fire,” Shenandoah Evening Herald, October 5, 1940.

Say, hello! Leave a comment!!!