Michael B. Scanlon makes your baseball encyclopedia as he was the manager of your Washington Nationals in 1884 (Union Association) and the Washington Nationals (National League) in 1886. However, Scanlon was referred to as the “Daddy” of D. C. baseball owing to his long association with the sport in the nation’s capital.

The native of Cork, Ireland came to Washington D. C. as the Great War for Slavery began. Coincidentally, the Nationals amateur club was formed two years before Scanlon arrived. And, a New York military company playing baseball in a Washington park in June 1861. Scanlon started playing the game soon after arriving in this country; he was involved with the Nationals amateur club as a member and director from that time, though he also was involved with other teams. In 1874, for example, he was the captain and shortstop of the amateur Creightons club. However, for much of his life, he was most associated with the Nationals, a club that alternated between amateur, semi-professional, and fully professional status for nearly thirty years.

Scanlon built a long friendship with Arthur Pue Gorman, the only man to have a greater influence over Washington baseball’s early days than Scanlon. In the years after the civil war, the Nationals became the first eastern team to go on a long road trip west, facing all the top teams throughout America. In 1868, the Nationals toured many cities, beating every team save one – a loss to the Forest Citys led by pitcher Albert Spalding. The business manager for that team on its road trip? Michael Scanlon.

Gorman was able to skirt rules against paying players by arranging to get players clerk positions in the federal government – thereby paying the players while giving them freedom to play ball and have an offseason job during the winters. The Nationals continued into the professional era, playing in the National Association in the 1870s (as did the Olympics, another very good “amateur” nine) and, while both teams left the professional ranks by 1875, they remained members of the National Association, which later operated a minor league in the east during 1879 and 1880.

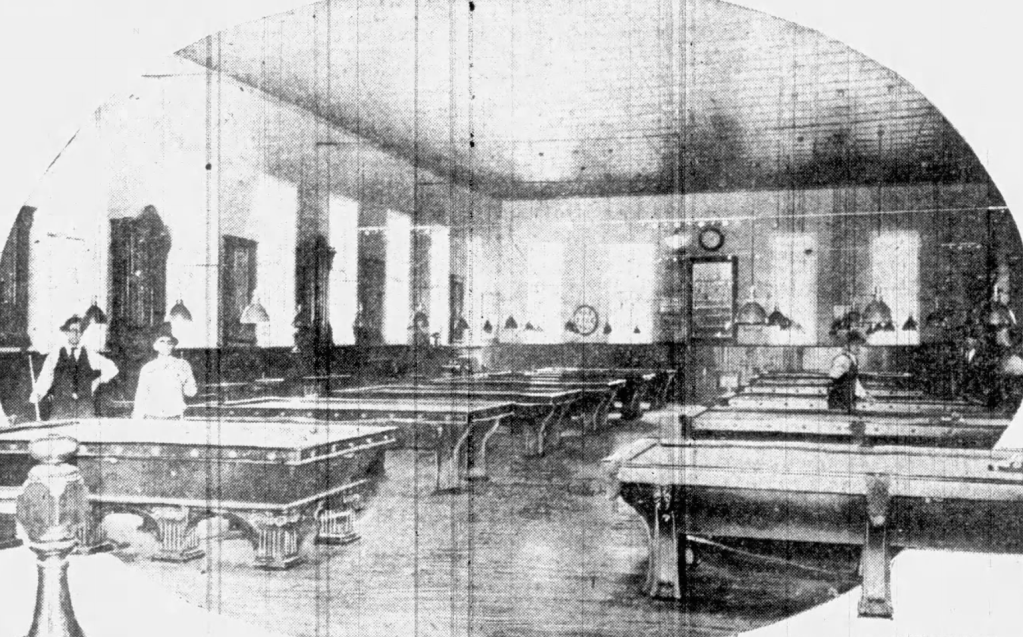

In 1879, Scanlon returned to managing the team as the field and business manager, earning praise for getting the team to play together. “Since Mr. Scanlon went East and took temporary charge of the nine a wonderful improvement has taken place, and the boys have won game after game under his careful coaching.” That team finished tied for second in the league but lost out on a chance to win the pennant when Springfield disbanded in September. Scanlon placed a scoreboard in front of his billiard parlor tracking games when he travelled. “The interest in receiving the news of the game has not abated, and the returns by innings are announced from nearly a dozen different places in the city. The crowd yesterday blocked the thoroughfare at Ninth and D streets, studying the bulletin-board in front of Scanlon’s, and when victory for the Nationals was assured the cheers and hurrahs were deafening.”

By 1880, he was an active director helping to organize team schedules at a national level. However, the Nationals, after a brief stint in the National Association, couldn’t seem to land a position in the National League. So, in June 1881 the professional team was briefly disbanded, much to the regret of one Michael Scanlon, who helped make sure that the team had no debts when it closed doors.

The Nationals returned to professional play, however, starting with a season in the Union Association in 1884. Despite some obstacles – starting with the American Association adding a team from Washington in hopes that it would keep the Union Association out of that city – the Nationals would prove to be competently run, both fiscally and on the field. Justin McKinney, who wrote a history of the Union Association, noted that one reason the Nationals succeeded was the frugality of Scanlon, who cut expensive players and found cheaper ones (who played better) – cutting the overall salary from an estimated $14,000 per year to about $7,000. (One way he was able to cut salaries was by using his government connections to get government jobs for players – he could pay them less during the season because the government was picking up part of the tab for the whole year.) The Nationals recovered from a 12 – 31 start and played slightly better than .500 the rest of the way, finishing 47 – 65 but well behind the St. Louis Maroons, who lost but 19 decisions all season.

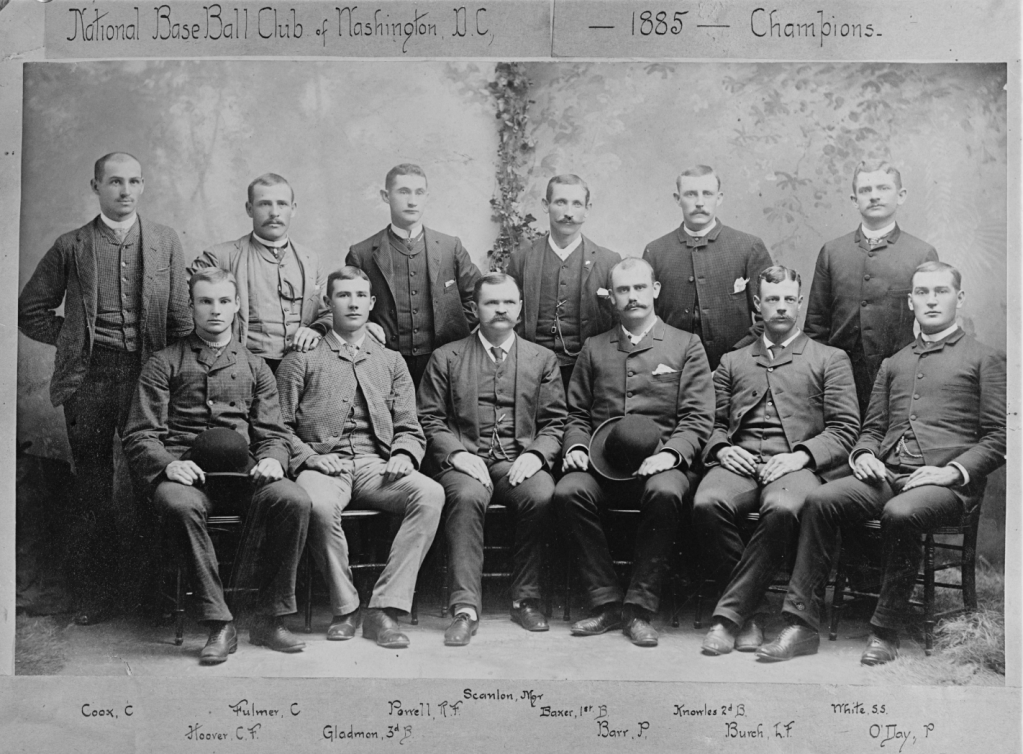

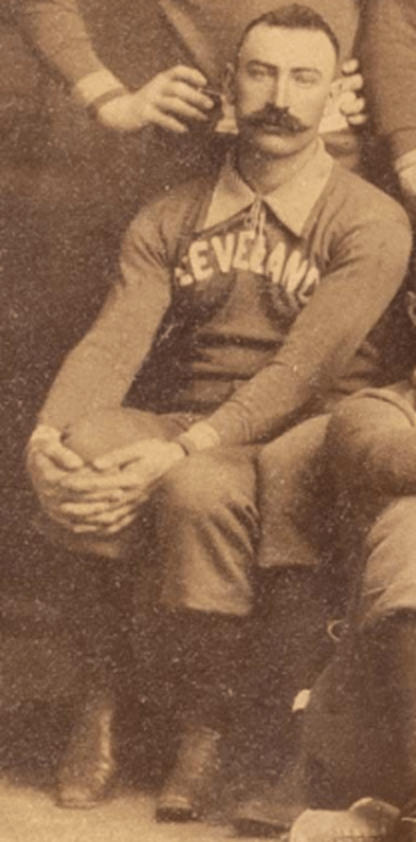

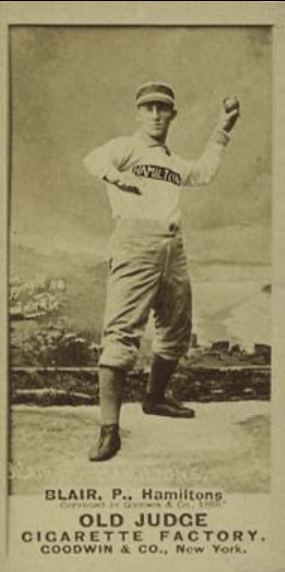

The Union Association died after that one season when the top two teams (and the majority of the financial backing) left for the National League instead. Scanlon and the Nationals also looked to join one of the other major leagues, hoping to land a berth in the American Association – in part because the Washington franchise that joined the Association disbanded without completing the season after losing 51 of 63 decisions. However, when that fell through the Nationals moved to the Eastern League, winning a pennant in 1885 with the team seen below.

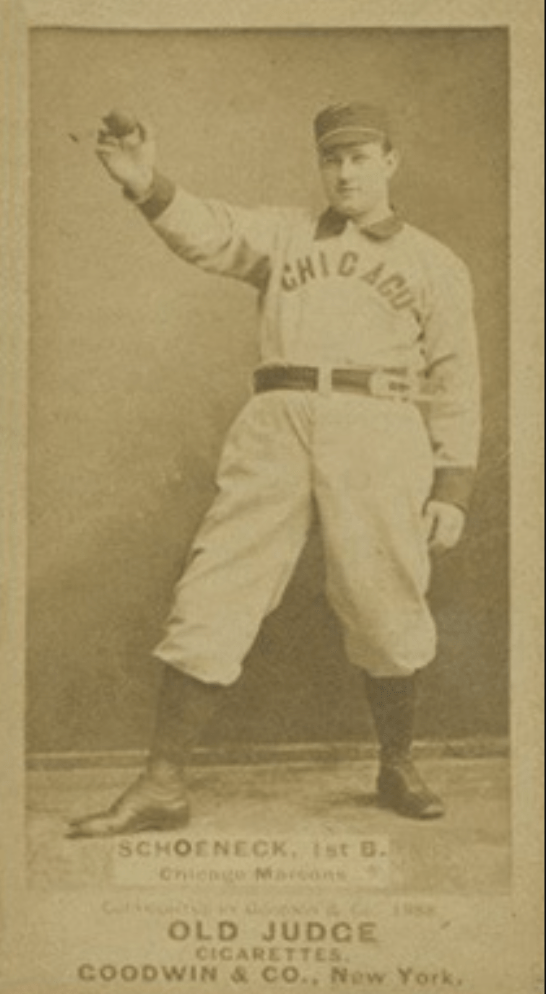

The Nationals finally got into the National League in 1886. Among other events during the season, Scanlon brought Connie Mack to the majors, paying $600 to Hartford to acquire the lanky young catcher. During the spring meetings, he was able to secure Paul Hines to join his club; Hines was the lone bright spot for the Nationals that year. Scanlon also acquired Hank O’Day, who pitched for Scanlon in both the Eastern League and the National League. O’Day later umpired major league games for several years (lower right, team photo below). O’Day is most famous for calling Fred Merkle out in a famous 1908 game.

Scanlon stopped managing the Nationals late in the 1886 season with the record standing at 13-67-2, turning over the team to John Gaffney, but he remained connected to that franchise until it folded in 1889. All told, Scanlon played, directed, owned, ran, or managed teams in D. C. for more than two decades. He returned to running his successful billiards location for the rest of his life – and had been the informal office of the Washington Nationals for more than twenty years.

One fun aside: Scanlon mingled with the presidents… Andrew Johnson watched the amateur Nationals during his term in the 1860s and would have the Marine Band play at their games. James Garfield was a big baseball fan – he stood in the crowds with all the other rooters and, while in Congress, helped find government jobs for ballplayers. And Ulysses S. Grant loved to play billiards. Scanlon, who opened his first billiards hall on June 1, 1867, helped Grant acquire and set up a table in the White House. Through two terms the genial Scanlon would often head to Grant’s table to play games with the President. In fact, Grant gave Scanlon a cue stick that Scanlon used for years afterward; he kept it on a rack in his billiards parlor. Scanlon and Cap Anson once tried to get Grover Cleveland to attend a game, but Cleveland passed asking what would the Amerian people think of a president who spent his time attending baseball games…

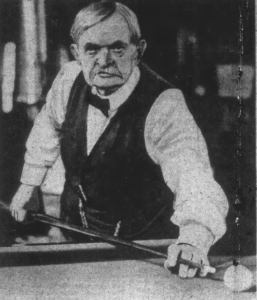

Scanlon married Nancy Bowler around 1870; combined they had six children, five of whom lived until adulthood (one was born to Nancy from her first marriage). As mentioned earlier, Scanlon owned a pool hall at the intersection of 9th and D Streets (NW) near the White House and was, himself, a remarkably talented shot. His parlor contained photographs and scrap books of the teams and games and players with whom Scanlon associated. For decades after he left his active role in baseball, Scanlon marched in parades, attended games regularly, and never lost his interest in the sport that defined his life.

On January 18, 1929, Scanlon died of a heart attack while walking the streets of Washington D. C. and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery there.

Sources:

1880, 1900, 1910, 1920 US Census Records

Washington DC Birth Records

Washington DC Death Certificate

Virginia Marriage Records

Virginia Birth Records

“Base-Ball,” Washington Evening Star, July 1, 1861: 4.

“Phelan Billiard Saloon,” National Intelligencer (Washington DC), May 31, 1867: 2.

“Phelan Billiard Saloon,” National Intelligencer (Washington DC), June 13, 1867: 1.

“Fun for the Boys,” Washington Chronicle, July 30, 1874: 5.

“Fifteen-Ball Pool,” Washington National Republican, December 18, 1877: 4.

“Base-Ball,” Washington National Republican, June 25, 1879: 4.

“The National Club at Home,” Washington Post, July 8, 1879: 1.

“Batting and Racing,” Washington Post, September 9, 1879: 1.

“Base Ball,” Washington Herald, April 25, 1880: 4.

“The Base-Ball Corpse,” Washington Evening Critic, June 17, 1881: 4.

“Base Ball,” Washington Evening Star, March 15, 1884: 2.

“Local Baseball,” Washington Evening Critic, December 16, 1884: 1.

“Old Fans Recall Days of National’s Triumph,” Washington Post, June 10, 1906: 2.

“Mack Started as a Senator,” Washington Post, January 26, 1913: 2.

George H. Dacy, “Washington as 1885 Pennant Winner Had Team of Famous Pioneers,” Sunday Washington Star, October 5, 1924: Magazine Section, Page 1.

“Champion Passes Up His Title,” Washington Times, November 3, 1926: 18.

George Summers, “Mike Scanlon—‘Daddy’ of D. C. Baseball,” Washington Post Sunday Magazine, November 13, 1927: 1, 5.

“$13,000 a Year Set High Cost Record for Nats in Old Days,” Washington Evening Star, July 3, 1928: 14.

“Mike Scanlon, Daddy of Baseball Here Dies; Picked Site of Griffith Stadium,” Washington Daily News, January 19, 1929: 22.

“‘Mike’ Scanlon Dies at Age of 81; Put Capital on Baseball Map,” Washington Herald, January 19, 1929: 9.

Say, hello! Leave a comment!!!