“Pepper was received with open arms by the public. He is a tall, well-made man, and stepped into the box with apparent confidence. His speed was tremendous at times. He fields his position well and displays skill as a batter…”

“Base Ball Jottings,” Indianapolis News, July 14, 1894: 8.

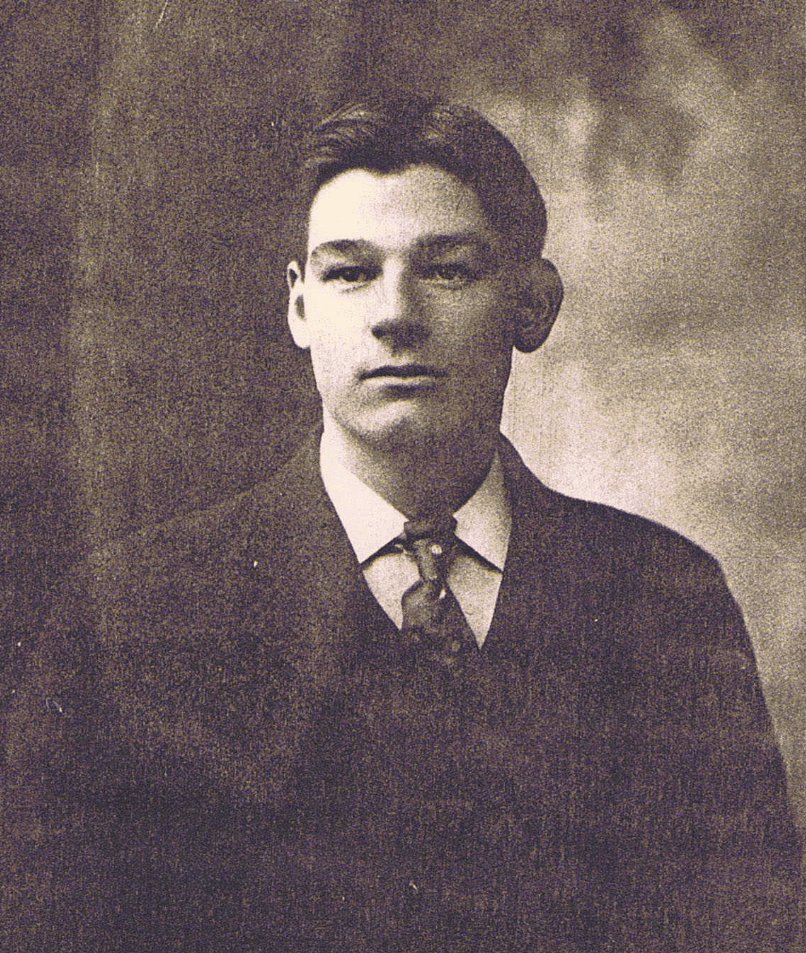

Harrison Pepper, initially a shortstop and centerfielder, became a pitcher under the tutelage of John McCloskey, helping Pepper get his major league shot with Louisville in 1894.

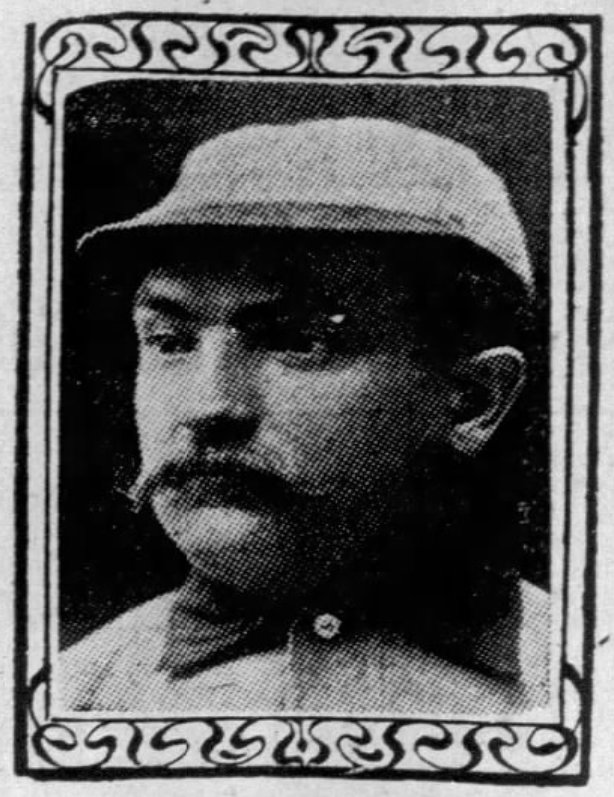

Baseball-Reference.com (and your old baseball encyclopedias) lists him as having been born in Kentucky in 1865, but other documentation suggests William Harrison Pepper was born September 2, 1864 to Samuel and Comfort (Jamison) Pepper in Calvey, Missouri on the farm where they lived when visited by enumerators for the 1860 and 1870 US Census records. Calvey was also the listed hometown when Samuel registered for the draft during the Great War for Slavery in 1863. (Likely confusing previous records keepers, an enumerator visting Harrison Pepper’s home in 1900 wrote down that Harrison was born in Kentucky.)

Harrison was the sixth of eight children born to the Pepper family. As noted, Samuel was a farmer – and though he registered with the United States army in 1863, given that one of his sons was named for Robert E. Lee, it’s just as likely Samuel Peppers would have served with the Gray as the Blue at the time he registered. In fact, this picture of Samuel Pepper could easily be mistaken for a member of Jesse James’ gang… Maybe not – Samuel left Missouri briefly to try his hand at farming in Bazine, Kansas. I lived in Kansas and I love that state. But Bazine is in the middle of nowhere (western Kansas) and regularly has a population south of 400 people. Which, then, makes it perfectly understandable that the Pepper family returned to Missouri and settled in Webb City.

Harrison Pepper got his baseball start in Webb City, which was good enough to win a regional amateur baseball crown in 1886 and joined an association of teams in southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas in 1887. Playing in local baseball circles while working in the local lead and zinc mines might have been the life of Harrison Pepper (and it would be a decade later), except he was very good. In the amateur leagues, Peppers could play any position on the field. He was a decent shortstop, a mobile centerfielder, and a smooth swinging left handed bat with enough power to generate a fair number of extra base hits. Years later, Pepper would win a case of Budweiser for hitting a far off advertising sign in the local Webb City baseball park.

In 1892, the Texas League was getting started. John McCloskey, manager of the Houston franchise, was a former major leaguer with a surprisingly good record for finding talent. To his credit, McCloskey was (a) willing to take a chance on anyone and (b) he recognized how other players could help him teach these rough prospects and turn them into productive players. For example, you might want to read how McClosky took a chance on Ollie Pickering, who literally begged for a chance to play anywhere and, when he got that chance, made like a hobo by riding cattle and pig cars for hundreds of miles to try out for the same Houston roster alongside Harrison Pepper.

Needing to improve his Houston pitching staff, McCloskey moved his strong-armed centerfielder and shortstop to the hill. McCloskey knew that Pepper would need an able catcher to work with him, so he convinced catcher Tub Welch to join the roster and serve as Pepper’s guru. This combination worked to perfection. Pepper went on to win 21 of 25 decisions – all while hitting .272 with decent power and stealing more than 20 bases. When McCloskey left for Montgomery in 1893, he brought both Pepper and Welch to the Southern Association with him. The Montgomery Colts got off to a great start – Pepper was undefeated in five decisions, the last a shutout over New Orleans, earning this bit of praise in a Times-Picayune article:

“Harrison Peppers, one of the pitchers, came into prominence with a hop, skip and a jump. Last season Peppers was signed by Houston to play short stop, but was one day put in to pitch. McCloskey noticed that the youngster would some day develop into a first-class twirler, and with the able assistance of ‘Tub’ Welch, who coached him, has come into prominence as a great man in his new position. He has good speed, fine control, and nothing can rattle him. He is also a good left-handed hitter and a big acquisition to the Montgomery team.”

“The Rise of the McCloskeys,” New Orleands Times-Picayune, April 27, 1893: 3.

When things soured (Pepper would lose his next four decisions) McCloskey did what he always did – he gave chances to other raw talents. One popular outfielder, Mike Shea, lost his job to Fred Clarke – yes, the future Hall of Famer. Harrison Pepper lost his job to a raw talent named Joe McGinnity, who in a few years would be launching his own Hall of Fame major league career with Brooklyn and New York.

Harrison Pepper would finish each season and return home to play ball closer to home. When his season was done in Texas, business people raised money to hire a good battery for a team in Joplin, Missouri – that money was spent, in part, on Pepper. In 1893, after he returned home from Montgomery, he pitched for his local Webb City club. In the offseasons, he returned to the zinc mines.

One quick note about Harrison Pepper. For some reason, his local papers and a couple of the Texas newspapers would spell his last name Peppers. However, his family name was Pepper. That’s what appears on his gravestone, many documents, and every newspaper covering his team from 1893 through 1895. For some reason, Peppers is what you see on Baseball-Reference.com and in some old encyclopedias It should be Harrison Pepper.

In 1889, Pepper married Annie McGhee, but that marriage fizzled with Pepper being on the road as often as he was when his professional baseball career got rolling. After the 1893 season, Pepper married divorcee Mary Jane (Sinclair) Bright. He would adopt her son and they, together, would have a son and a daughter, Ivie and Caroline, in 1894 and 1898, respectively.

In addition to having his first child, Pepper’s baseball life would be busier in 1894 than in any other season. He began the season pitching for Savannah – John McCloskey was put in charge of the team and he called on some of his old friends, including Pepper and Fred Clarke, to join the roster. Pepper was put into a rotation with former major leaguers Toad Ramsey and Martin Duke, though Pepper was frequently called on to finish games that the other two failed to finish. As such, when Savannah’s franchise folded in late June, Clarke and Pepper were given an opportunity to try out with the Louisvile Colonels of the National League.

You might have read about Fred Clarke’s first game with Louisville. Facing the Phillies on June 30, 1894, he had five hits, demonstrated tremendous range in left field and wielded a strong and accurate throwing arm. On that same day, Harrison Pepper pitched three innings of relief, giving up a run on three hits and demonstrating a bit of wildness (three walks). On July 6, Pepper got the start against the New York Giants and Amos Rusie. Pepper was swatted around, eventually getting pulled in the fifth inning. And with that, Louisville decided that Pepper wasn’t ready for the big leagues. A few days later, he was on his way to Indianapolis to pitch for the Hoosiers in the Western League.

Manager Bill Sharsig had one pitcher that he trusted, Bill Phillips, and was hoping to find a second as he needed to replace Lem Cross, who was recalled to Cincinnati. Harrison Pepper proved equal to the task. He made 24 starts, finishing all but one, and going 11 – 12, which was a big improvement from the 6 – 21 record shared by a handful of other pitchers who were given 29 starts to see if they were good enough to pitch in the Western League. Among Pepper’s most interesting wins was a 33 – 23 win in Minneapolis on August 30. 56 runs!!! Minnesota shared the eight innings of work amongst four pitchers (as per rules of the time, Minnesota chose to bat first), Sharsig left Pepper out there for all nine innings – 53 batters faced – and only two spots in the Minnesota batting order had fewer than three hits. One was the right fielder, Willie Wilson, who went two for four and drew two walks, and the other was the pitcher’s spot – except that the third pitcher of the game, Norm Baker, got two hits himself in just three at bats. Pepper walked 8 batters – so he had to throw, what, 225 pitches, right?

Pepper not only pitched well enough for Indianapolis, but he also hit .292 with three homers, finishing with a .510 slugging percentage. However, he wasn’t good enough to take turns in the field where Indianapolis could have gotten more use out of his batting skills. He played two games in the outfield, one of which was apparently disastrous. The Indianapolis News wrote, “…Pitcher Pepper went into right field. His playing in that position was grotesque, and nobody seemed to know it better than he. He tried hard, but he didn’t know that position.”

And once, due to an umpire not being available for a game, Pepper was called upon to be the base umpire for a game between Indianapolis and Detroit, while former Indianapolis pitcher and current Detroit pitcher Robert Gayle called balls and strikes. There were many skirmishes over close calls. The Indianapolis Journal felt that Gayle was definitely making decisions for his own team’s benefit while Pepper tried to be fair. (Gayle may have felt the sting of having been released by Indianapolis earlier in the season, too.) When Gayle killed a Hoosier rally by calling a third strike to end the eighth inning, a pitch that the Indianapolis Journal writer thought was three feet outside, the game was lost to Detroit.

When the 1894 season was through, St. Paul’s Charles Comiskey showed an interest in Pepper and traded the rights to Bert Cunningham to Louisville to get the rights to Louisville’s former prospect.

As the 1895 season began in St. Paul, the lack of a full spring training meant that when Pepper pitched, Pepper pitched in pain – such as when Pepper was picked to pitch to the Picketts and got pounded in a practice game. Pepper opened the season with a mixed bag of outings, and then he had a couple of really bad outings, giving up 25 runs (22 earned) to Milwaukee to end May, followed by 12 runs in three innings to Detroit. In that second game, manager Charles Comiskey refused to waste another pitcher and told Pepper in no uncertain terms to get his rear in gear. Pepper didn’t give up a run the rest of the way. However, it was soon discovered that Pepper wasn’t necessarily happy pitching in St. Paul (they had gotten off to a rough start and it’s not clear how much he liked the city). Indianapolis was willing to bring back Pepper. And local Indianapolis articles said Pepper deliberately pitched poorly so as to get released by St. Paul so he could sign with Indianapolis.

Comiskey called him out – told Pepper he had a contract that he had to honor, threatened to suspend him without pay, and then publically humiliated Pepper by leaking this story to the St. Paul Globe. Pepper had no choice but to ask for forgiveness, say he never intended to leave the team, and started pitching better. His best outing was a shutout win over Grand Rapids on July 13 – reportedly the first time Grand Rapids had ever been shut out. In fact, a Grand Rapids furniture maker promised to make a custom chair to the first team to blank Grand Rapids; later on a dice game determined which Apostle got to keep the chair. Pepper scattered eight hits and his fielders played a nearly flawless game. In fact, when the season was over Pepper led St. Paul in starts, was only six innings shy of leading the Apostles in innings pitched, led his team in wins with 21, and, had he not pitched those two brutally horrible games, would have had a more enviable stat line. By the way – Pepper could still handle the bat. When not pitching, he frequently took a turn in the outfield – sometimes batting cleanup – and finished the season with a .269 batting average and three homers.

With that, Pepper went home to his family and decided his days pitching professionally were over. He would work in the zinc mines and play for the local semi-pro team in Webb City instead. In 1897, rumors came about that he was entertaining opportunities to play in St. Paul or with McCloskey in Texas, but none of the local papers in St. Paul or Dallas mentioned it.

Still, Pepper occasionally found his way into the local paper. Once, during a local storm, a bolt of lightning struck his home. The lightning entered through the screen door and set the ceiling on fire (it was quickly extinguished). The lightning strike so shocked Mary Jane, who was seated nearby, and she dropped Ivie to the ground.

The Joplin Daily Globe carried a story about a night in which Pepper was robbed.

“Two bold highwaymen, of the dime novel sort, made their appearance at Webb City Saturday night. They held up Harrison Peppers with a pair of ugly looking guns and went through his pockets. Five cents was their reward and they returned that. On West First street they held up Will Earls, getting $2 in money from him. He put his gold watch in his hat, however, and got away with it all right. The robbers will be better posted on the ways of Webb City next time in all probability.”

Sometime in the summer of 1902, Pepper came down with the symptoms associated with tuberculosis. At various points over the next year, he would travel to Seattle or Hot Springs, Arkansas hoping to change the course of the disease, but with little success. Adding to his suffering, Pepper developed stomach cancer. By October, 1903 his health turned far worse and on the morning of November 5, 1903, just 39 years old, Pepper moved on to the next league. The Knights of Pythias, of which Pepper was a member, assisted with the funeral at Webb City Cemetery, where Pepper’s earthly remains lie.

NOTES:

1860, 1870, 1880, 1900 US Census Records

US Civil War Registration Records, Missouri

Missouri Marriage Records

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/peppeha01.shtml

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49396760/william_harrison_pepper

“Webb Citys,” Carthage Banner, May 19, 1887: 3.

“The Players Assigned,” Galveston Daily News, April 24, 1892: 4.

“To Secure a Battery,” Joplin Herald, July 13, 1892: 4.

“The Rise of the McCloskeys,” New Orleands Times-Picayune, April 27, 1893: 3.

“The Last of Base Ball,” Savannah Morning News, June 29, 1894: 3.

“Can’t Win Always,” Louisville Courier-Journal: July 1, 1894: 3.

“Took Two Straight,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 7, 1894: 3.

“Maybe Three Straight,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 11, 1894: 5.

“Base Ball Jottings,” Indianapolis News, July 14, 1894: 8.

“Fourteen to Nothing!,” Indianapolis News, July 20, 1894: 8.

“Thrown Down Again,” Indianapolis Journal, August 8, 1894: 3.

“Broke All Records,” Indianapolis Journal, August 31, 1894: 3.

“Comiskey is Here,” St. Paul Globe, March 15, 1895: 6.

“Play Ball Today,” St. Paul Globe, April 15, 1895: 16. (Includes captured image of Pepper).

“Western League Notes, St. Paul Globe, April 22, 1895: 6.

“An Extra One,” St. Paul Globe, June 1, 1895: 5.

“Pep is Peppered,” St. Paul Globe, June 12, 1895: 5.

“Pepper Passed Up,” St. Paul Globe, June 14, 1895: 5.

“Hot Dose for Pepper,” St. Paul Globe, June 15, 1895: 5.

“Diamond Dust,” St. Paul Globe, June 17, 1895: 5.

“’Twas Great Ball,” St. Paul Globe, July 14, 1895: 5.

“A Local Pitcher’s Rise,” Carthage Press, July 5, 1894: 7.

“Neighborhood News,” Carthage Evening Press, April 8, 1895: 2.

“About Town,” Joplin Herald, June 21, 1895: 5.

“Neighborhood News,” Carthage Evening Press, September 27, 1895: 4.

“Sedalia Wins Two Games,” Carthage Press, May 7, 1896: 9.

“Missouri Points,” Kansas City Journal, March 29, 1897: 4.

“Personals,” Joplin Daily Globe, August 7, 1897: 8.

“Base Ball for Joplin,” Joplin Globe, August 28, 1897: 2.

“The City,” Joplin Daily Globe, September 9, 1897: 3.

“About Town,” Joplin Daily Globe, October 10, 1899: 5.

“A Birthday Surprise,” Joplin Daily Globe, September 4, 1902: 8.

“Goes to Seattle,” Joplin News-Herald, November 26, 1902: 5.

“Webb City Briefs,” Joplin Globe, August 5, 1903: 7.

“An Old Citizen Gone,” Webb City Register, November 5, 1903: 2.

“Harrison Peppers Dead,” Webb City Daily Sentinel, November 5, 1903: 1.

“Harrison Peppers Dead,” Joplin News-Herald, November 5, 1903: 5.

Say, hello! Leave a comment!!!