If you read any of the nostalgic views of Yankee players and seasons at the end of Mickey Mantle’s career, a period in which the Yankees lost its luster and fell all the way to tenth place in a ten-team league, you get the idea that the face assigned to that period is a kindly young man with a soft, but heavily southern accent, and a name that carries with it a bit of whimsy. That name is Dooley Womack.

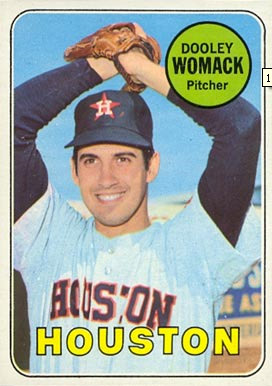

The person responsible for it was none other than his own teammate, pitcher and writer Jim Bouton. At the time, Bouton was keeping his diary of the season he spent with the Seattle Pilots trying to put his career back together in the bullpen while learning to throw a knuckleball. In late August, Bouton was sent to the Houston Astros for Womack and minor leaguer Roric Harrison. Bouton’s entry noted his surprise and mocked Womack.

“Maybe it’s me for a hundred thousand in cash and Dooley Womack was a throw in. I’d hate to think that at this stage in my career I was traded even up for Dooley Womack.” – Ball Four

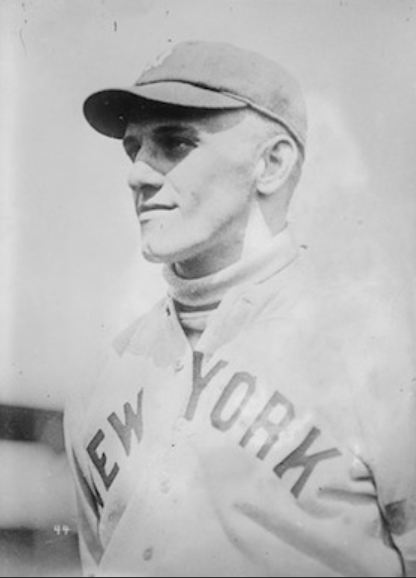

Born August 25, 1939, Horace Guy Womack hailed from Columbia, South Carolina where he attended Brookland-Cayce High School and played all sports, but excelled as a pitcher. The name Dooley was hung on him by a childhood friend and it stuck. Signed by the Yankees for $2500, he was sent to St. Petersburg in the D-League for the 1958 season and then spent eight seasons working his way up through the minors, including stops in the C-Level Northern League in Fargo-Moorhead, Greensboro in the B-Level Carolina League, and Augusta in the A-Level South Atlantic League.

The 1963 Augusta Yankees, for which Dooley was a reliever, won the Sally League but still lost money (as it had many seasons) and wound up closing down. Womack remembered that the team had one key offensive play. Leadoff hitter Ronnie Retton (Mary Lou’s dad) would reach base. When he would take off for second, Ike Futch would bunt down the third base line and Retton would race all the way around to third. The defense would be so flustered that they would invariably throw the ball away and Retton would score easily.

Womack was a reliever, having been shifted away from the rotation because he would seem to tire after about six innings. Traveling scouts suggested making Womack a reliever and Womack found success. However, he also felt like he was being ignored by the Yankee management. So after the 1964 season, he sent a letter to the Yankees saying that he was done with baseball and would be taking an office job in Georgia.

That year, Womack won ten games and saved 13 others in 50 appearances. He also served as a pinch hitter, batting .291. “I’ve had three pretty good years in a row,” he told a reporter in a wire story that was printed in the Toledo Blade. “But I’ve never gotten a crack at Triple A ball. I feel sure I can do the job. Let’s face it, the guys who are playing in the International League are the same ones I was getting out in the Southern League.”

The reason Womack was overlooked was because he was a smallish six foot tall, never weighing more than 175 pounds. He threw a sinker and slider for strikes and a fastball that wouldn’t overpower most batters. However, he kept the ball down and could contribute in other ways. “If you are a fair bunter and hitter it gives you a chance to stay in the game. Me, I’ve always liked to grab a bat.”

The Yankees also knew that there was a lot of interest in the savvy reliever, so they decided to add Womack to the 40-man roster and agreed to move him up to AAA Toledo in the International League. At Toledo, he was among the league’s leaders in ERA, and later in the season, when called upon to make a few starts, he rattled off several good outings in a row, earning a trip to his first big league spring training in 1966, where he made the team.

Womack remembered that his locker was closest to the door, a reminder that he could be sent packing at any time, and that the only veteran to greet him was Mickey Mantle. “Mantle came all the way across the locker room and shook hands.” Mantle also once thanked Dooley for his relief efforts the day he hit his 500th home run. “Thanks for letting me enjoy my 500th,” the Mick told Womack. “If we had lost it would have been awful quiet.”

Womack was one of the few bright spots on that 1966 team, a team that fell from winning the AL pennant to the basement of the American League. Tony Kubek’s sudden retirement, injuries to Whitey Ford and Roger Maris, and a very slow start put the team in a tailspin from which they could never recover. However, it allowed Womack to take a larger role in the bullpen. After spending a winter in Puerto Rico, where he was coached by former Yankee Luis Arroyo, Womack became the team’s closer. In 1967, Womack, increased his save total from four to eighteen, winning five others in relief, and appeared in 65 games, tying a team record. At one point, they referred to Dooley as The Mini-Vulture, a play on the nickname of reliever Phil Regan. “I don’t care what they call me as long as I can do the job I’m supposed to do,” Womack said.

Womack spent the winter with his wife, Janelle, in New York City, enjoying a few workouts with the team at Yankee Stadium in the winter, hitting the speaking tour, and once handing out subway tokens with other Yankees as part of a marketing ploy. It was the first time Womack had seen snow, and the kind southern boy fit in well in the big city. “My wife, Janelle, and I sort of shook when we first thought about living here. First of all there was this big difference in climate and we’d heard about what to expect from New Yorkers,” Womack explained. “Well, we’re used to the climate and we found out most of the tales you hear about the people here aren’t true. They’ve been simply wonderful to my wife and me.”

Such heady days were few, however. He held out, hoping for a larger contract in the spring of 1968, and then struggled with a sore shoulder. Getting off to a slow start, he lost his closer role to Joe Verbanic and later Lindy McDaniel, but still contributed in the late summer by getting his ERA, near 5.00 in May, down to 3.21 at the end of the season. And, he was involved in a rare triple play against the Twins. Johnny Roseboro lined back to Womack with the bases loaded. Womack fired to Bobby Cox at third, who rifled a throw to Mantle at first to complete the first Yankee triple play in nearly two decades. However, Ralph Houk and the rest of the Yankee management had other options and Womack was traded to Houston for Dick Simpson, an outfielder who didn’t get along with Astros manager Harry Walker and was now with his sixth franchise in seven years.

Womack pitched well enough for the Astros, a fun bunch of guys who would play pranks on players and come up with silly reworded songs about each other. “Hang down your curve, dear Dooley” would be chanted when someone hit one of Womack’s curves harder than planned. Another time, Dave Rader called Womack pretending to be San Francisco manager Clyde King, telling Dooley to find the traveling secretary to get a plane ticket right away. Dooley wasted no time finding Art Perkins, who said he knew nothing about it, but Rader’s inability to keep a straight face gave away the prank.

In August of 1969, Womack was traded from Houston to the Pilots for the last six weeks of the season. It was more like a loan – he returned to Houston only to be sold again to Cincinnati. The Reds kept him as sort of an insurance policy in 1970, where Womack played for AAA Indianapolis, showing success. When the Oakland A’s lost reliever Jim Roland to a knee injury, Oakland purchased Womack’s contract. Dooley got two more major league appearances, in each case getting swatted around, and earned a ticket to Oakland’s AAA Iowa team in 1971. When the season was over, so was Womack’s baseball career.

At first Womack sold clothing. “I had pitched before 50,000 people, and now I was trying to sell one guy a pair of pants,” Womack said. “It was a bit of a comedown.” After trying real estate, Womack next started selling commercial flooring – a job that stuck for more than 20 years, until he retired.

Now, 40 years removed from his last days as a baseball player, Bouton’s attitude toward Womack seems to have the longest lasting effect. When someone offered thousands of dollars to charity for the temporary naming rights to the Fleet Center in Boston, giving it the name of Derek Jeter, a writer suggested that a Yankee name like Dooley Womack would have been more acceptable. Another Tribune article talked about “…kids who knew the ERAs of obscure pitchers like Dooley Womack…”, and another article said that George Steinbrenner “…lifted [the Yankees] from the horror of the Horace Clarke/Dooley Womack era.”

Unfair, certainly, but it keeps Dooley Womack in the memory of Yankee fans and that can’t be too bad. Besides, one look at his career numbers and you see a pitcher who lasted five years in the big leagues with an ERA under 3.00 in over 300 innings of work. People line up to get his autograph or shake his hand. And he appears to be more welcome at Yankee reunions than, say, Jim Bouton.

Leave a reply to Paul Proia Cancel reply