Once in a while you get a fun genealogical treat when researching the life of some virtually unknown (at least unknown to you) ballplayer. Today is one of those days, as I dug into the life and times of Kansas City Cowboys catcher Ward Dwight.

For years, he has been known to your encyclopedia compilers as Al Dwight. And, while I’m not saying that he didn’t play under the name of Al Dwight – he very may well have done that. However, Baseball-Reference.com shows his full name as Albert Ward Dwight and that is wrong. So, let’s go about correcting a few things.

Ward Alonzo Dwight was born on August 1, 1855 to Alonzo Dwight and Adelia (Hoadley) Dwight, bringing Ward into this world in Windsor, New York. Alonzo was a farmer and lumber dealer – something his family did in the United States for a long, long time. In fact, you can backtrack through the Dwight family tree all the way back to John Dwight, who came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635. Over the generations, which includes a brigadier general, the Dwight family moved west – eventually settling in upstate New York.

Alonzo Dwight died in 1867, leaving Adelia to finish raising their six children, of which Ward was the last arrival. Adelia was the mother of the last two children. Alonzo originally married Adelia’s sister, Betsey Hoadley; Alonzo and Betsey had four children before her death in 1852. Ward got a pretty complete education, attending the Amenia Seminary. Ward wasn’t headed to the pulpit, however. He was headed for the pulp… Wood pulp. that is.

“An anti-cremation society, of Chicago, was also licensed under the name and style of the Marble Burial Case Manufacturing Company; capital $100,000. Ward A. Dwight, Taylor E. Daniels and Seymour Coleman, incorporators.”

“The State Capital,” Chicago Inter Ocean, August 11, 1877: 5.

Partnering with his brother-in-law, Seymour Coleman, they started their own lumber dealership in Chicago, featuring the sales of coffins. Around 1890, completing the western trek of his wing of the Dwight family tree, Ward and Seymour took their business to Portland, Oregon, where Ward worked for seven years. He then moved his offices to San Francisco. Along the way, Ward married Mamie Fowler in Chicago in 1877 and they had one son, Ward Alonzo Dwight, Jr. The son would start his own electrical business, running that out of his father’s office in San Francisco until he took over the family lumber business upon his father’s passing.

“The Spaldings… have secured the services of Dwight, an old time catcher, who will play third base for them in place of Irwin, who joined the Rivals.”

“Amateur Notes,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1889: 12-13.

Now, with rare exception, I write baseball biographies and this is no exception. Ward likely learned the game of baseball in New York, where the modern game took a hold throughout the state. He brought that with him to Chicago. You can find a number of box scores throughout the 1880s with Dwight behind the plate stretching all the way to 1890. One article noted that Dwight was, at 34, an old-time player.

The Union Association ran for but a single season, 1884. And, as luck would have it, the Altoona franchise folded in early June and its spot was taken by a new franchise in Kansas City. A couple of the Altoona players who had ties to the river city went west to join the Cowboys. The rest of the roster was filled by the best available players of the Midwest.

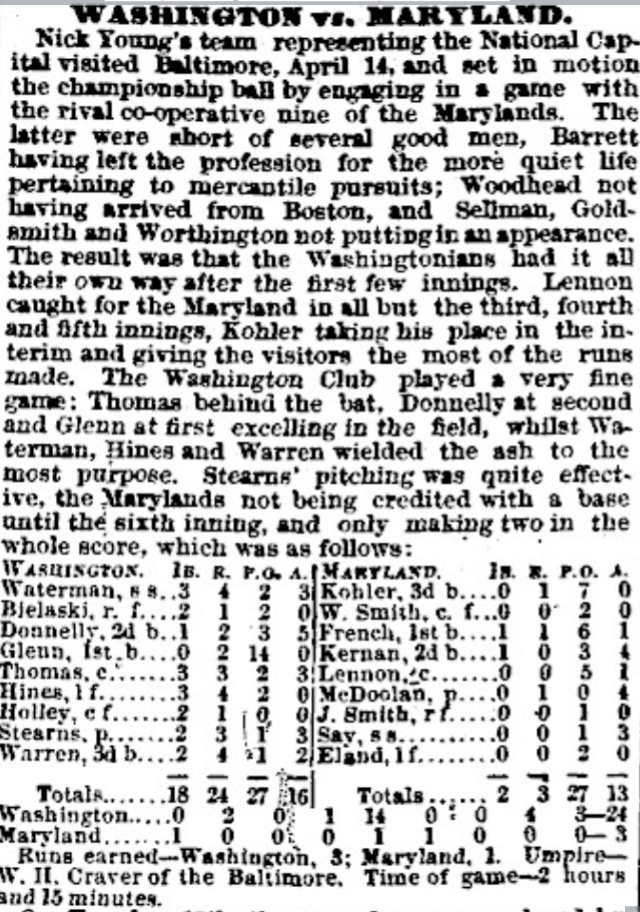

“Dwight made a good impression behind the bat, putting out eight men and catching four long bounds.”

“Chicago Unions, 12; Kansas Citys, 3,”

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 20, 1884: 8.“…Dwight had some trying work behind the bat and acquitted himself well.”

“Sport,” Kansas City Journal, July 6, 1884: 2.

Ward Dwight (he may have played under a different name, Al, so as to separate his baseball and business lives) signed with the Cowboys and took a spot behind the plate. He wasn’t half bad, really. Dwight batted a weak .233 but his overall contribution was slightly below league average. Of the seven players who worked behind the plate for Kansas City, he had the highest batting average and the highest fielding percentage. His career, however, lasted just twelve games and barely five weeks. He would return to Chicago and play amateur baseball.

Still, swinging the lumber was a hobby and selling the lumber was his life. So, when an opportunity to deal in lumber on the west coast came up, he laid down the mask and got on the train.

Of the articles I found about Dwight (and his partner/brother-in-law Seymour Coleman), many involved legal wrangling around product usage, but one stood out from the lost and found column. Dwight lost a red Moroccan wallet containing some $300 in it. So, he placed an ad asking someone to return it to a Pinkerton office and collect a $50 reward for bringing back the wallet and its contents to its rightful owner.

As the century turned from the 1800s to the 1900s, Ward Dwight began suffering from heart disease, regularly having chest pains. Despite pleas from his wife, Dwight boarded a train to Portland for business on February 14, 1903. He stayed the night in the Hotel Cactus, and later went down to the bar on Sunday afternoon. Ward told the bartender that nothing he tried could make his chest pain go away, and that he was having trouble breathing. The barkeep suggested adding bromide to his whiskey order, but before he could serve the drink Dwight fell to the floor – the bartender seeing his arm for a split second before Dwight’s body was out of sight. Doctors couldn’t save him – Dwight passed to the next league at 2pm on February 15, 1903.

His son took charge of his body and Ward Alonzo Dwight’s remains were sent to be buried in the family plot in the Spring Forest Cemetery in Binghamton, New York.

Ward, Jr. took over his father’s business. In 1922, he sold the lumber company to California Pine Box Distributors for more than $120,000 (about $4.5 million today). He would later start a new business in Yuma, Arizona. Ward’s grandson, also Ward Alonzo Dwight, played golf in the San Francisco area and for two decades was regularly seen in the local papers for winning club and regional tournaments – starting with a Presidio Club title while still in high school.

One assumes the youngest Ward A. Dwight was especially good with his woods.

Naturally.

Sources:

1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900 US Census Data

1855, 1865, 1875 New York Census Data

1898 San Francisco City Directory

1900 California Voter Registration

Henry Porter Andrews. “The Descendants of John Porter of Windsor, Conn. 1635-1639,” G.W. Hall Book and Job Printer, 1893: Page 740.

Lineage Book of the Charter Members of the DAR, Volume 071.

Cook County (IL) Birth Certificate Index

Amenia Seminary Faculty and Student Lists, 1873

Return of a Death (Portland Oregon)

“The State Capital,” Chicago Inter Ocean, August 11, 1877: 5.

“Federal Courts,” Chicago Tribune, February 14, 1880: 7.

“Law – Judge Smith,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 18, 1883: 7.

“Lost and Found,” Chicago Tribune, June 6, 1884: 11.

“Chicago Unions, 12; Kansas Citys, 3,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 20, 1884: 8.

“Sport,” Kansas City Journal, July 6, 1884: 2.

“Short Stops,” Kansas City Times, July 28, 1884: 2.

“City League Averages,” Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1887: 14.

“Amateur Notes,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1889: 12-13.

“The Club League,” Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1890: 2.

“Dead in an Instant,” The Oregonian (Portland), February 16, 1903: 12.

“Died at Portland,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 16, 1903: 10.

“Deaths,” Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1903: 11.

“Notice of Trustee’s Sale of Real Property at Public Auction,” The Reedley Exponent, March 29, 1922: 7.

“Big Golf at Presidio,” San Francisco Bulletin, November 6, 1922: 22.

“Ward Dwight Wins Northern California Handicap Golf Title,” Oakland Tribune, May 21, 1923: 19.

“State of California, Department of State,” Yuma Weekly Sun and the Yuma Examiner, December 17, 1937: 12.

Say, hello! Leave a comment!!!