“It will not be surprising to discover after a few weeks’ playing that the association has signed several old timers under assumed names. Candy Nelson of Brooklyn is said to have signed with some new organization down this way. Candy has blue eyes, old gold hair and store teeth, and if discovered palming himself off as an ambitious youngster it will go hard with him.”

“Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, 28 March 1895: 6.

This was written five years after his last major league appearance – Nelson was already 46. When the US Census took data in 1900, Nelson still listed his current job as that of a ball player.

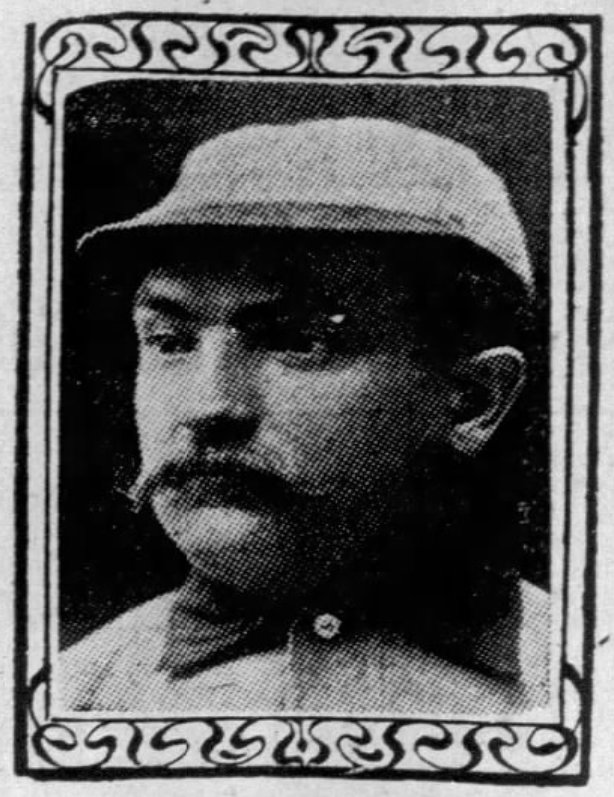

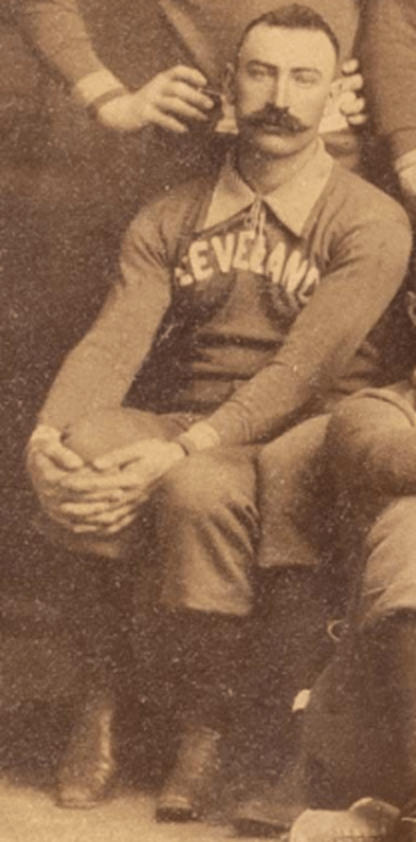

John W. (Candy) Nelson was born Portland, Maine on 14 March 1849, the last of six children of Peleg and Mary Nelson. Peleg was a merchant and familiar with the world of shipping having worked on ships for years, eventually becoming a “master mariner.” To his credit, he built up a successful business and some familial wealth before moving to Brooklyn as the Great War for Slavery approached.

Candy played top level amateur ball in Brooklyn and New York (by 18, he was a shortstop for the Eckfords in 1867) before logging his first season in the National Association in 1872. Though, sometimes his youth got in the way of his play – especially in 1868. In an 1868 game against the Irvingtons, Nelson’s attitude had been becoming a problem when he was finally called out for his behavior.

“But what can be said in extenuation of Nelson’s conduct?,” wrote a reporter with the Brooklyn Daily Times. “Recently this player has got so irritable and disagreeably insulting in his remarks, both to the umpire and his fellow players, that we were glad to see him rebuked for his wilfullness during he game. He got miffed at a play of Wood [Jimmy Wood, the Eckford second baseman], and when a ball was knocked to him a moment afterwards, instead of making an effort to stop it, on which he could have made a double play, he let it pass between his legs. ‘Time’ was called, and he was gently informed that if a similar instance of willful bad play occurred again, he might consider his position in the nine vacant.”

“Base Ball Items,” Brooklyn Daily Times, August 8, 1868: 3.

He switched to the New York Mutuals in 1870, and was now playing third base instead. Nelson did put one over on his old teammates that May. In a 22 – 8 thrashing of the Eckfords, “…Nelson took the liberty of hitting the ball so hard, and making C. Hunt run so far, that he was credited with a home run.” Even though Nelson batted in the middle of the lineups at this point in his career, a home run was a rare event. While the Mutuals were, in fact, a professional team in an established organization, it wasn’t a “league” game per se. He wouldn’t hit a professional home run in a league game until 1881.

Nelson returned to the Eckfords in 1871; it was there where you first see Nelson batting at the top of the order rather than the middle. The Eckfords were professionals (a number of players would play in the Natioanl Association in the coming seasons), but they weren’t members of the Association for that first league season. That said, they held wins over the Philadelphia Athletics, Chicago White Stockings and Nelson’s old New York Mutuals club – the latter was a shutout victory. The next year, the Eckfords would join the ranks of the “major league” thus turning the professsional ballplayer to someone with an entry in your baseball encyclopedia or website.

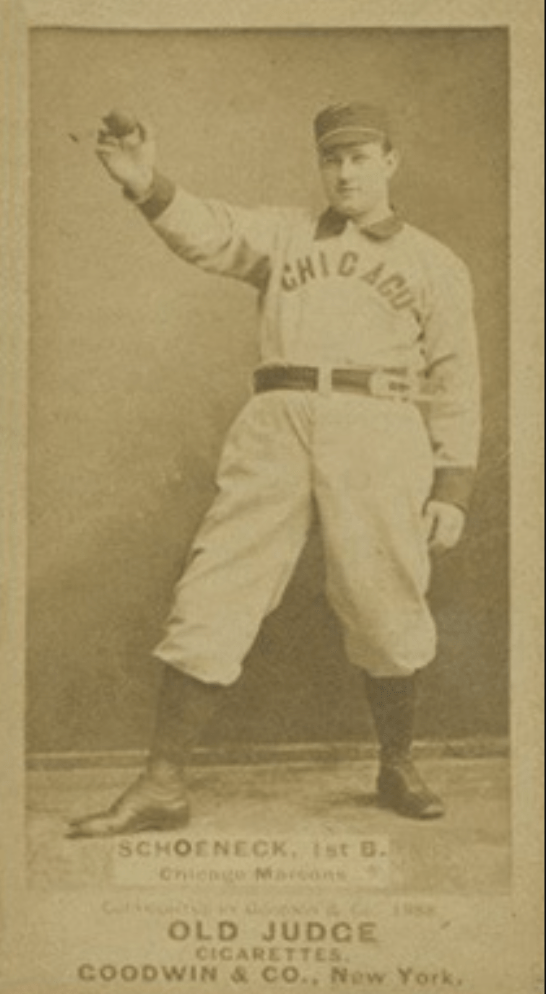

At first, Nelson and a few other teammates (Jimmie Wood, George Zettlein, Charley Hodes and Count Gedney) left the Eckfords to join the Troy Haymakers. Nelson’s time with Troy would be all of four productive games before Troy disbanded and he (and many of his friends) returned to the Eckfords for the remainder of the 1872 season. Nelson returned to the New York Mutuals for the next three seasons until the Association was supplanted by the National League. At first, Nelson was a hitter. He batted .327 for the Mutuals, but he fell off drastically in 1874 and hit just .199 in 1875. This cost him his big league job.

After two seasons playing with an amateur team called the Nameless club in Brooklyn (and taking on a wife – see below), Nelson returned to the majors, landing with Indianapolis of the National League. He again struggled at the plate, batting all of .131. So, as one might expect, he returned to the Nameless club in his hometown. Later in the summer of 1879, needing some help, Nelson was signed by the new National League Troy franchise. Nelson played a respectable shortstop while batting .264 and getting on base enough to bat about 20% better than his peers. That said, Troy had a new third baseman in the name of Roger Connor (future home run king and Hall of Famer) for 1880, so Nelson was allowed to move on.

He didn’t go far from home for 1880, playing for the Unions semi-professional club in Brooklyn and occasionally sneaking in a game with other amateur teams. By the end of the season, he was playing short for the New York Metropolitans. He even played in the first game at the original Polo Grounds when it opened for baseball in September, 1880. He stayed in the New York area playing on amateur nines (very good amateur nines) for 1881 and 1882, save for a 24 game stint with Worcester at the end of the 1881 season where he batted .282 and, along the way, he hit his first major league home run. Nelson hit it off of Detroit pitcher George Weidman, the change pitcher for the Wolverines, on September 27, 1881.

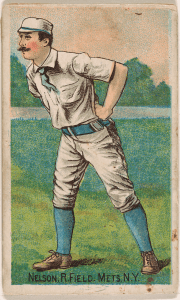

Nelson returned to the Metropolitans in 1882 – by now a professional team without a spot in a major league. Soon, however that would change and the Metropolitans would join the American Association for 1883. For the next five seasons, Nelson would play his most consistent baseball in the major leagues, 493 games at shortstop – starting at the age of 34 years old.

Candy Nelson was more than just the 19th century Derek Jeter. He was also a bit like Max Bishop. He led the National Association in walks once, albeit with just nine, but he took it to a new level in the mid-1880s. Despite tolerable (but low) batting averages, he was a lead off hitter because he would draw a lot of walks – leading the league twice in 1884 and 1885. And, he was a daring baserunner throughout his career – regularly stealing bases and taking chances on the basepaths throughout his career. As a member of the 1884 Metropolitans, he faced Providence in the first “World Series” between the American Association and National League champs.

By 1887, he was pretty much done as a regular shortstop. He was released by the Metropolitans – but he did sneak in a game with the New York Giants in 1887. This should have ended his career, but he continued to play in New York and Brooklyn on top semi-professional nines until 1890. And, when the major leagues expanded to include the Players’ League, the Brooklyn Gladiators signed the 41-year-old Candy Nelson to play shorstop. He appeared in 60 games, batting .251 with a .365 on base percentage. And he wasn’t done… Nelson was listed on an Eastern League roster in 1893 and amateur teams after that.

As for the nickname, I haven’t yet found the source. It doesn’t show up in coverage until his major league career was nearly over, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t in use throughout his career.

Nelson married the former Eliza Guischard in 1876; they had one daughter, Lydia, two years later. During his career, Nelson opened and ran a cigar shop. Not long after his career ended, he was living off passive income – even declaring that he was retired to the New York State Census enumerator in 1905.

Nelson passed away at 61 years old in his adopted Brooklyn home on 04 September 1910, probably wishing he could still play ball. His earthly remains lie in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Baseball-Reference

1905 New York Census

1850, 1860, 18790, 1900, 1910 US Census

New York Marriage Index

FindAGrave.com

Image Source

“Sporting Items,” Brooklyn Daily Times, July 20, 1867: 1.

“Base Ball Items,” Brooklyn Daily Times, August 8, 1868: 3.

“Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Times, May 21, 1870: 3.

“Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 1, 1871: 2.

“The Haymakers,” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1872: 5.

“Personal,” Brooklyn Daily Times, January 25, 1873: 4.

“Ball and Bat,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 15, 1879: 4.

“Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 14, 1880: 3.

“Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 27, 1880: 3.

“Base Ball on the Polo Grounds,” New York Times, September 30, 1880: 8.

“Detroits, 11; Worcesters, 6,” Boston Globe, September 28, 1881: 5.

“Spiders, Bugs, Jiggs, Rats, Colts, Stars,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 7, 1893: 23.

“Old Ball Player Dies,” Brooklyn Daily Times, September 5, 1910: 10.

Say, hello! Leave a comment!!!